Antonio Giannini and Maria Modena Giannini |

|

A brief introduction to the first members of our family in America -- |

|

This ship is of the period of the "Triumph", so probably similar to the one on which Antonio Giannini and Maria Modena arrived in America. (Philadelphia Maritime Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) |

In early September, 1773, the frigate Triumph sailed from Livorno

(Leghorn) in Italy with Italian entrepreneur Fillipo Mazzei, his new wife and

stepdaughter, and ten Italian vignerons, or vineyard cultivators, including Antonio

Giannini, then 26 years old, with his wife Maria Modena Giannini, their 2-year-old

daughter Maria Caterina, and Maria's brother, Francis Modena. The ship also had a

hold full of cuttings, seeds and tools. They arrived at a port in the James River,

four miles from the Epp's place, which was described as being four miles from

Williamsburg, in late November. A notice of their arrival was printed in The

Virginia Gazette. Mazzei had grand designs for establishing a wine, olive oil

and silk business in the moderate Virginia climate, and hoped this voyage was the

beginning. Mazzei planned to settle in the westernmost parts of Virginia, on Thomas Adams' plantation in Augusta County, and left the workmen to go ahead to scout out the site. On the way he stopped at Monticello and Jefferson was immediately taken with the Italian visitor: the next morning he took him to see two parcels of land adjoining Monticello to the East, one of which was available for purchase, and to which Jefferson added more acreage as a gift. This land is the site of what became Mazzei's Virginia home, known as Colle. And thus a settlement of Italians, including Antonio Giannini and his wife and daughter, arrived in Virginia two years before the revolution. A second group of Italians arrived the following year, many of them recruited, Mazzei said, by what Antonio Giannini had written in his letters home. Among the second group was Carlo Bellini, who would become the first Professor of Modern Languages at the College of William and Mary. One of the best descriptions we have of life at Mazzei's plantation, Colle, located a short distance from Monticello, was provided by Isaac Jefferson, who worked as a nail-maker at Monticello, in his "Memoirs of a Monticello Slave." He describes Mazzei's nice frame house built by his workmen, the worker's huts made of saplings and mud, about which Isaac says: "People in dem days didn't have sense enough to make laths", and their plentiful vegetable garden. He also comments on the bounty of the Italians' meals, saying they prepared "more victuals" than Isaac had ever seen. Mazzei eventually became so caught up in the cause of revolution that he offered himself as an envoy to travel back to Europe and seek support for the cause. When he left, some of his employees went to work for Jefferson, and one of them was Antonio Giannini. Antonio stayed in Jefferson's regular employ until after the revolution, living somewhere at Monticello, most likely the group of worker's houses known to have existed on Mulberry Row. He remained at Monticello from approximately 1778 through 1793, and continued to work off and on for Jefferson into the early 19th century. While Jefferson was in France, he wrote several letters to Antonio, giving him instructions and asking how things were going. Antonio's letters to Jefferson, in Italian, with which Jefferson was conversant, have also been preserved. Antonio apparently shared Jefferson's love of the written word. One entry in Jefferson's account book records that he paid Antonio "$1 for damage to a book." When Antonio inventoried his possessions in 1824, he counted every item down to the individual teaspoons, but his library he simply lists "all my books of every description." Antonio was paid slightly less than an overseer. Peter Hatch, Director of Gardens and Grounds at Monticello and author of The Gardens of Monticello and Thomas Jefferson's Flower Garden at Monticello, says he was employed primarily as a skilled grafter. The letters also indicate he was supposed to make trial bottles of wine using grapes from Jefferson's vines. In one letter he complained that Jefferson's people kept picking the grapes too early, and he had no authority to stop them, so the wine couldn't be made that year. The current Assistant Director of Gardens and Grounds, Gabriele Rausse (who is in many ways a latter-day version of Antonio, having come from Italy to work at another Virginia vineyard in 1983) has another view. He thinks the problem was more likely wild animals eating the grapes, either before or just when they ripened, as birds, deer, and foxes are all fond of grapes at differing stages of ripeness. When Antonio's second son was born, and given the middle name of Tomei, or Thomas, Jefferson wrote a jubilant entry in his account book giving Antonio "45 gals. of whiskey...as committee for Francesco Tomei," which must have afforded quite a celebration. The connections between the families continued for generations. Antonio and Maria's first granddaughter was a godchild of Jefferson's daughter, and in 1853, Jefferson's nephew , also named Thomas Jefferson, would inform the court clerk of the death of his neighbor, Antonio's first son, Nicholas, correctly giving both parents' names, and stating that Nicholas was born "at Monticello," again at "Mulberry Row." A court deposition by one Christopher Hudson of July 26, 1805, relating to an earlier time when Jefferson fled Monticello during the revolution as the British were approaching, states that the last person with Jefferson at Monticello was "his gardener." We don't know for certain that this was Antonio, but he was the gardener of record at the time. There are also family stories about Caterina Giannini carrying meals to Jefferson while he was in hiding, which may be apocryphal but are cherished in the family nevertheless. We do have proof of Antonio's devotion to his new country in the fact that he joined the Albemarle County militia, and was paid for 44 days active duty during the march to and the Battle and Surrender at Yorktown. Jefferson's account book reveals that Antonio was with the Virginia militia from September 10 through October 24, 1781. After the revolution, Antonio bought several parcels of land in the Buck Island Creek and Blenheim area, one of which he sold to James Monroe to become part of his Ash Lawn and Highland plantation. In his 50s, when Antonio was using the Americanized name Anthony Gianniny, he was ordained by the Baptist church and licensed by the state to perform marriages. For the next 15 years his name is most often found in the court records in association with that duty. We have not been able to determine for certain which congregation he served, but his officiating duties covered Albemarle, Louisa and Nelson Counties. New information suggests he may also have been ordained as a Methodist minister, officiating in Amherst County in that role. In his later years he settled in Nelson, near two of his sons. Antonio and Maria raised eight children, and their descendants over the years since then number 3,000 or more. The most recent family reunion was held August 7-8 in Charlottesville, and an article about it is in the latest issue of the family newsletter Vines and Branches. Finally, the television show "Falcon Crest," about a family of Italian winemakers in California, was inspired by family stories of Antonio and Maria's lives in Virginia, and written by a descendant, Earl Hamner, Jr., who also created the beloved Waltons of Walton's Mountain from family history. |

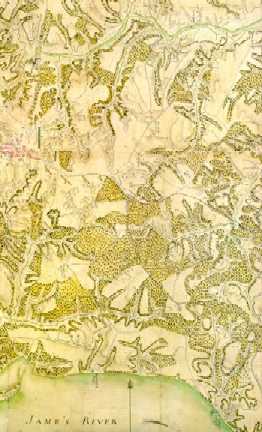

An overall map of the area where Antonio and Maria landed, showing a little of Williamsburg also, drawn by a French soldier in September, 1781. On the dirt roads of the day the distance from the landing place to Williamsburg is about eight miles.

|

|

A detail from the map above, showing Trebell's Landing & Burwell's Ferry, where Antonio and Maria are believed to have first set foot on New World land. Not shown is the location of Epp's place, from which written records indicate the landing place was four miles. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.) |

|

Colle, the plantation Mazzei built near Monticello and where Antonio worked, in 1930 just before it was demolished. |

|

Archaeology at Monticello in about 1979-80,showing where the garden and vineyard was located. This photo and the one below are courtesy of the archaeologist Dr. William M. Kelso. |

|

Bottles are period wine and spirits bottles from about 1770-1790, excavated from Mulberry Row where the first Gianninis probably lived. One of the bottles still contained cherries and liquid -- something Antonio may have prepared!

|

|

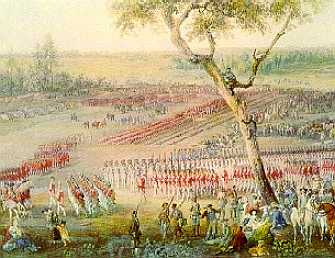

A scene of the surrender at Yorktown, depicted by a French soldier. The landscape must be similar to what Antonio saw.

|

|

Another view of the Yorktown surrender, by the same French soldier, showing more landscape details. (from Rochambeau's Travels in North America, 1780,1781,1782,1783.) . |

|

One of the many families that came together at the 1999 Reunion. (Click picture for caption in Vines & Branches.) |

|

|

Home | News | Family introduction | Join the Giannini Family List | The Giannini's of Virginia, 3rd Edition | Antonio as Minister | | Vines & Branches newsletters | Links | e-mail |

|